Takitaki mai comes from the phrase ‘ka takitaki mai te ata’ which speaks to the harbingers of morning’s arrival. The art and science of the motivational practitioner is to pick up and enhance the glimmer of new dawns.

Authors

Dr Eileen Britt – (PhD, PGDipClinPsych, FNZCCP, MNZPsS) Registered Clinical Psychologist;Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychology/School of Health Sciences, University of Canterbury. Member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers

Daryl Gregory – (BA, Cert in Community Psychiatric Care, Cert in Social Work) Waikato/Hauraki; Chairman of He Waka Tapu Board of Governance Christchurch

Tohi Tohiariki – (MNZAC, MNZAP, DAPAANZ Accredited Clinical Supervisor) Te Arawa and Whānau A Apanui; Assistant Director/Clinical Oversight Salvation Army Addiction Services, Christchurch

Terry Huriwai – Te Arawa and Ngāti Porou; Advisor, Matua Raki, National Addiction Workforce Programme

Acknowledgements

Tukua te wairua kia rere ki ngā taumata Hai ārahi i ā tātou

Me tā tātou whai i ngā tikanga a rātou mā Kia mau kia ita!

Kia kore ai e ngaro Kia pupuri

Kia whakamaua

Kia tina! Hui e! Tāiki e!

E ngā mana, e ngā reo, e ngā pātaka o ngā taonga tuku iho, ngā uri o ngā mātua tūpuna, tēnā koutou. Tēnā koutou i roto i ngā āhuatanga o te wā. E mihi ana ki te hunga kua huri ō rātou kanohi ki tua o te ārai, ki te tini e hingahinga mai nei i te ao i te pō. Nā reira, me kī pēnei ake te kōrero, tukuna rātou kia okioki i runga i te moenga roa, rātou te hunga wairua ki a rātou, tātou ngā kanohi ora ki a tātou. Tēnā koutou, tēnā tātou katoa.

The authors acknowledge the concepts in this document are developed from the original writings from Miller, W. R. and Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change to addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press and recognise the ongoing contribution of William Miller and Stephen Rollnick in this area.

The passion of Joel Porter combined with the desire of Matua Raki, the National Addiction Workforce Programme, to improve the accessibility of MI for Māori working in the addiction sector led to an opportunity to facilitate MI training in Aotearoa for Māori and Pacific practitioners. This in turn was a catalyst for Takitaki mai. The work of Kamilla Venner, who developed the Native American Guide to Motivational Interviewing, also served as a foundation for this work.

The authors also acknowledge the feedback on an early draft from colleagues in the addiction treatment sector. Given his experience facilitating the Māori and Pacific MI training the invaluable feedback of Steve Martino reflected not only his expertise in MI but also his appreciation of the New Zealand context and the application of MI within a Māori and Pacific therapeutic milieu.

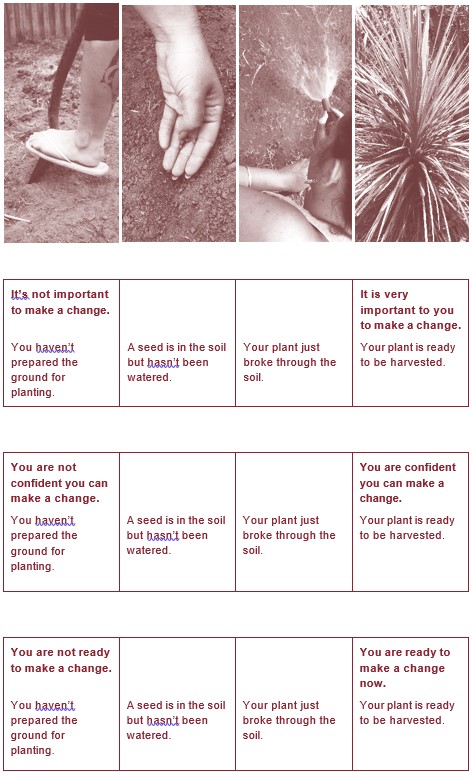

The photographs used are from the private collections of He Waka Tapu and He Waka Tapu staff members as well as relevant stock photos.

Introduction

The purpose of this guide is to bring Motivational Interviewing (MI) to Māori working in the health and social service sectors. As a way of working, the authors believe MI offers much to enhance the work of Māori practitioners – particularly those working with Māori. Although the authors draw on their experience of utilising Māori concepts, values and practices, they recognise and acknowledge that Māori working in the health and social service sectors have a range of understanding and capability to use this knowledge in their work. It is outside the scope of this guide to explore Te Ao Māori concepts or practices used as part of the therapeutic process. However, Appendix 1 is an adapted reading and resource list from the Takarangi Competency Framework (Matua Raki, 2012) that practitioners can use to enhance their knowledge through self-directed learning.

The guide grew from the philosophy of He Waka Tapu (Appendix 1) incorporating images of journeys and pōwhiri processes, a Matua Raki MI training opportunity and a collaboration between like-minded parties wanting to increase the accessibility of MI to Māori. He Waka Tapu uses the image of waka – a symbolic image of whānau moving into the future. He Waka Tapu invites men and women to consider what kind of waka will carry them and their tamariki into the future. What kind of waka needs to be built to face the many and varied challenges? Who is going with them and what skills will they need to ensure success? Do they know how to get there? What navigation knowledge or instruments do they possess?

He Waka Tapu kaimahi also have an understanding of the ‘pōwhiri process’ which provides the backdrop to all engagement and relationship building with whānau. This involves a series of transactions with the intention of creating a safe physical, emotional and spiritual space that allows a transition from tapu to noa, and also space in which kōrero can take place.

The purpose of this guide first and foremost is to contribute to maximising positive outcomes for Māori. This guide is aimed primarily at Māori practitioners wanting to utilise MI. Ideally practitioners will already be taking a holistic approach to health and wellbeing, based in Māori beliefs, values and rituals. It is hoped this guide will mean MI is used more effectively within Māori settings. Our desire is for a Māori approach to MI that is readily transferable to a broad range of health-related issues and ‘user friendly’ for both kaimahi and whānau.

Some areas in which MI has been found to be useful are:

- addictive behaviours g. substance use, gambling, tobacco use

- asthma

- diabetes

- diet and exercise

- stopping violence

- hypertension

- medication use

- oral health

- reducing

Culture, Healing and Motivational Interviewing

Māori, like other indigenous people, have used holistic healing interventions based in their knowledge systems to ameliorate physical problems as well as disruptions of the spirit, emotions, and of the mind. Understanding illness and wellbeing requires consideration of the underlying values, philosophy and ideology that influence both the seen and unseen manifestations of distress and wellbeing. A transformational

practitioner must be aware of cultural symbolism, process (particularly communication and relationships) and metaphor if they are to help a person navigate their own path to wellbeing.

A culturally competent practitioner can contribute to wellbeing by integrating cultural and clinical elements within their practice. Linking indigenous culture and knowledge with other theoretical models is possible when the goal is hope, wellbeing and transformation. At the end of the day it is about best practice.

Also like other indigenous populations worldwide, Māori have and currently experience historical, cultural and socioeconomic deprivation and trauma that impact on their collective and individual wellbeing. Often strangers in their own lands, many indigenous people have had their cultural knowledge and understanding eroded or lost, thus one should not assume all Māori are the same. However, even when whānau appear not to be engaged with things Māori, many can and do respond to Māori processes and/or ways of being. It is important for practitioners not only to think about Māori that present in terms of cultural context or potential trauma, but also as part of a system or collective.

Healing and transformation are centred not just on diminishing ‘illness’, but also on creating paths toward wellness. For Māori, identity is a central element to wellbeing and, as a collectivist culture, ideas of self are entwined in the group. Rather than the emphasis being on the individual’s desires and achievements, Māori place more value on relationships within the group – obligation and responsibility to and for others.

Competent practitioners take these understandings and move beyond ritual to integrate cultural knowledge with deliberate therapeutic intent. Taking time to greet others and show respect is important, and when combined with competencies like karakia, pōwhiri and whakawhanaunga, they create safe spaces physically and spiritually for the therapeutic relationship to occur in. Ensuring these processes changes the nature of the relationship. Therefore practitioners working with Māori, whether using MI or other talking therapies must orient their practice to sit within a cultural milieu that is Māori.

These processes and the underlying principles whakamana (empower) the client and their whānau, promote interdependence and contribute to relationship-oriented thinking. These complement MI, which creates a respectful and supportive counsellor- client relationship, emphasises collaboration and encourages whānau to find their own path towards balance and wellbeing. Using knowledge of Māori processes with MI can help Māori clients and whānau have their experiences and worldviews validated.

In general, MI seems to be a good fit with ways of interacting and working with Māori. It is hoped this guide will help build practitioners’ cultural competence by enhancing their ability to utilise MI within a Māori cultural context.

The Pōwhiri Process as the Therapeutic Frame

In pre-European times, rituals of engagement were used to determine the intention of visitors; whether they came in peace or war. Through a progressive series of stages the intentions of the visitors became clear and could subsequently be managed with the least amount of risk to all concerned. Various models utilising the process or principles of the pōwhiri within the therapeutic frame exist and have been articulated over the years, such as: Pōwhiri Poutama (Te Ngaru Learning Systems, 1995); Pōwhiri as a competency within the Takarangi Competency Framework (Huriwai, Milne, Winiata et al, 2009); a framework to enhance the doctor-patient relationship (Lacey, Huria, Beckert et al, 2011) and in relation to self-harm (Hatcher, Coupe, Durie et al, 2011). All these ‘models’ have similar elements and a consistent purpose relating to the processes of encounter, engagement, and relationships. The process of pōwhiri in the therapeutic context is to create a safe space (including a transition from tapu to noa), build relationships to establish trust, and develop a therapeutic alliance.

As well as the symbol of a waka and the notion of journey, He Waka Tapu, as noted earlier, also sees the importance of the engagement process – thus the importance of the pōwhiri. The pōwhiri process provides a framework for practitioners to review and reflect on their practice.

Pōwhiri

Within the pōwhiri, the rituals of encounter also take into account what happens ‘outside the gate’. For many people the preparation for a pōwhiri might include knowing the reason for the gathering, the names of the hosts and the venue, finding out about the kawa and whakapapa of the marae, deciding who will speak and what waiata might provide the kinaki to the speeches.

“I am interested in what whānau needed to do to get here, how have they prepared themselves? What do they know in regard to the kaupapa? How did they overcome any resistance or hinderance they had to arrive at my door, and what part of them does want to be here? Did they do any homework about who I am, what I do, how we operate etc. I am really interested in how much work they have done prior to arriving, that’s the kōrero I want to have so I am careful not to get engaged in other types of kōrero such as the nature of their referral etc too early. This is what I call ‘outside the gate’ work.” Daryl Gregory

For many, the wero is a reminder of safety but it is also where a practitioner might lay down the first challenge or taki. When the whānau accepts the taki they acknowledge they are ready to proceed and understand what it is they are saying and entering into.

“For me, picking up the taki is a sign that whānau are prepared to take responsibility for their behaviour and their potential for change. Ascertaining if whānau are presenting in a way that they are ‘standing on the taki’ or demeaning it or are prepared to step up and explore the presenting issues is important. It may be that considerable time is spent at this stage – this can be thought of within the pōwhiri process as ‘standing at the gate’.” Daryl Gregory

For some the first karanga might be the call to the service – the invitation to participate. After the wero the karanga is a symbol of an exchange of information at a deeper level and it’s a beginning to weaving wairua and other elements together, whakapapa, history etc. It is also part of a transition from the ritual of encounter to the ritual of engagement.

The whakaeke can be seen by practitioners as a response to the karanga, and also a chance to ascertain whether there really is any movement taking place, or whether people are just physically moving forward but on all other levels they are still ‘outside the gate’. Monitoring body language as whānau move upon the domain of Tū also encourages practitioners to check out who is walking with the ope – physically and otherwise.

It’s also an opportunity to check out how they are moving – are they coming freely or with reservations, or are they just going through the motions? During the whakaeke people will pause to reflect on a range of things including the passing of loved ones etc. This is a timely reminder for practitioners to pause and reflect on what is happening, checking in and getting a real sense of where people are at.

The last transition of the pōwhiri process moves people from the ritual of engagement into the ritual of relationship. It is in this part of the process that people formally move from tapu into noa. The key elements are the whaikōrero, the hongi and kai. Whaikōrero is the exchange of kōrero that includes a range of things such as whakapapa, our history with each other, what do we need to know, what might get in the way of us agreeing on the kaupapa, do we agree on what the kaupapa is, have we been here before and what happened then that might come up again now?

The hongi is where the hā or breath of life is exchanged and intermingled. Through this physical exchange the visitors become one with the tangata whenua. The hongi is a sign of life symbolising the action of Tāne’s breath of life to humans. By this action the life force is permanently established and the spiritual and physical bodies become a living entity.

“Hongi reminds me to clarify that through the process of pōwhiri we have entered and share a place of joining. This and kai frees us from restrictions and enables us to commit to the kaupapa.”

Daryl Gregory

A successful pōwhiri process will enable elements of the spirit of MI as well as allow a more effective use of MI. The following are concepts and practices that enhance the He Waka Tapu understanding and practice of pōwhiri as part of the therapeutic process.

Whakataunga

This is the stage where there is a reflection on what the key points of the discussion have been thus far and a consolidating of any change talk in MI terms. Have we landed in a good place to go forward, or do we need to pause as mentioned? This can be likened to the evoking process in MI.

He kokonga whare e kitea

He kokonga ngākau e kore e kitea

A corner of a house may be seen and examined, not so the corners of the heart

Karakia

Karakia is a process of acknowledgement and invocation of divine energy. It is a key that opens a pathway between our earthly nature and our spiritual nature. ‘Ka’ means to energise. ‘Ra’ connotes the divine spark of energy and ‘Kia’ means to be. In other words, “Let us become infused with energy from a divine source”.

In the context of MI, karakia may be used for a number of reasons such as at the beginning to clear a spiritual pathway and provide a spiritual ambience for the mahi. Karakia can also be used during a session to bring calm or for guidance; and at the end of a session(s) for safety and the future. Understanding the therapeutic intent of karakia dictates how and when it might be used. The following is an example of one such karakia:

Ma te hau mahana o te kāhui o te rangi Me te wairua o ngā tūpuna

Tātau e Tiaki Tātau e manaaki i ngā wā katoa

May the warm winds of the spiritual realm and the spirits of our ancestors guide and take care of us always.

What is Motivational Interviewing?

Developed by William Miller and Stephen Rollnick,

MI is an active, whānau-centred way of being with people. MI is not a technique, but rather a facilitative, guiding style. Research has found that this style can increase the natural desire of whānau for change.

MI is a collaborative conversation for strengthening motivation for change. MI allows the whānau to talk about his/her ambivalence about changing behaviour in such a way that the balance is tipped towards positive change. MI does this by paying particular attention to the language of change (see the section on Change Talk).

The following are some key ideas behind MI.

- Whakawhanaunga is essential for engagement and

- MI honours the wisdom within the whānau instead of trying to force any kaimahi ‘agenda’ upon the whānau.

- The whānau is seen as a collective doing the best they can, rather than a set of problems. The whānau identifies and processes their own thoughts and feelings both for and against changing current circumstances.

- The kaimahi provides māramatanga (clarity) in helping the whānau examine and move forward with their thoughts and feelings about change.

- Persuasion is not an effective method because trying to convince others to change often invites them to argue against change.

- Often people are in two minds about changing a behaviour – this is normal and to be expected.

- The MI style is gentle and draws the wisdom forth from resources already existing within the whānau.

- Motivation is not static. Instead, it changes depending on internal and external factors (family and friends, community, job, finances, mood ).

- The therapeutic relationship is more of a partnership, kanohi ki te kanohi, (face-to-face as equals) rather than an expert talking down to a client.

Why Motivational Interviewing?

Ma te whakatau, ka ora ai

When you know the signs, healing can begin.

MI is a whānau-centred guiding style. It is a dynamic interactive relational process for developing and strengthening motivation for change. MI helps whānau explore and resolve ambivalence (being in two minds). It is a brief intervention (1-4 sessions) which can be used with individuals, or within groups. Group MI requires the combined skills of both MI and group process. For more information on MI in groups see Motivational Interviewing in Groups (Wagner and Ingersoll, 2013).

Research has shown MI to be effective for a range of behaviours, particularly alcohol use disorders, but also other health behaviours such as diet and exercise. This research shows MI can be effective as an intervention in its own right (helping whānau find the motivation to change may be all that is needed for them to change) or as a preparation for another intervention.

Research has also found that MI has a greater effect for ethno-cultural groups, particularly those groups who have experienced marginalisation and societal pressure. Given the excellent results of MI with other indigenous peoples and positive experiences of utilising MI to good effect with whānau, there is some confidence that this is helpful in working with Māori. Elements of MI are ‘tikanga consistent’ and so can be used to complement tikanga approaches.

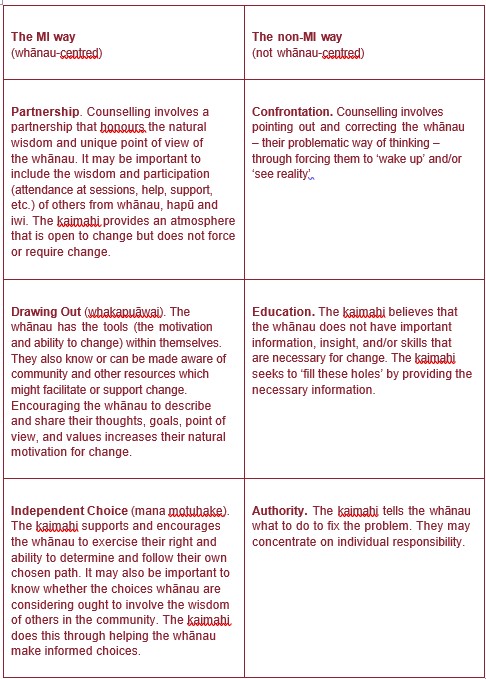

The following contrasts an MI way with a non-MI way of working.

Learning Motivational Interviewing

MI might be easy to learn if:

- you are familiar with Māori beliefs, values and practices

- you honour the wisdom and resources that are already within whānau

- you are a good listener

- you expect and accept that whānau may be in two minds about changing a behaviour

- you value mana motuhake (self-determination) by the whānau

- two of the core attitudes you model are whakamana (an attitude of empowering whānau) and whakaiti (an attitude of humility)

- your primary focus is on whakawhanaunga.

Research shows learning MI takes more than attending a workshop. If you want to learn MI and integrate it into your work to produce better

outcomes for whānau, then feedback and coaching after workshop training is recommended. This guide is designed to supplement workshop training and coaching MI.

Some key steps to learning MI are to:

- unlearn old habits – such as asking questions (rather than reflecting)

- slow down – trying not to rush to fixing things, instead taking time to listen to the whānau

- be humble – avoiding being the expert and instead see the whānau as an equal partner

- believe in them (the whānau) – believe in their potential for change

- reflect – going with their language about change

- become comfortable with silence

The Spirit of Motivational Interviewing

The first aspect of the spirit of MI is partnership. It is a shared journey between a kaimahi and whānau. The kaimahi has MI skills and the whānau has strengths and this combination contains the seeds for oranga (health, wellbeing).

Te rongoā tūturu o ngā tūpuna i te kōrero

The original medicine of our ancestors is to share our experiences with one another.

The second aspect of the spirit of MI consists of acceptance. This includes honouring the autonomy (mana motuhake) of the whānau. In other words, it is ultimately up to the whānau to decide whether they want to or how to make changes. Accepting also involves recognising and valuing the absolute worth of the whānau. Acceptance is conveyed through accurate empathy, and through the use of affirmations.

Thirdly, MI is practiced with compassion (ngākau mahaki). In other words, it is practised with the best interests of the whānau at heart.

Evocation (whakapuāwai) is the fourth aspect of the spirit of MI. To evoke is to ‘bring forth’. The intention is for the kaimahi to assist the whānau to actualise their potential and bring forth their underlying motivations for wanting things to change. This means in practice that the whānau should be talking a lot more than the kaimahi.

In this guide, we begin with the spirit of MI and then turn to various skills and techniques. We want to emphasise that the ngākau (heart) of MI is its spirit – without the spirit, MI is not being practised and the results are not as likely to be effective.

Me whakaaro tātou ki te wairua, kāore ki te kupu anake

Consider, think or feel the wairua, not the word alone.

Processes in Motivational Interviewing – Ngā Pou

MI can be thought of as having the following four fundamental processes, with each building the foundation for the subsequent process.

- Engaging (whakawhanaunga) – along with unlocking the wairua, this process of (re)establishing relationships involves the transition from tapu to noa, and is essential. Engagement needs to continue throughout the session(s).

- Focusing (whakamārama) – where the kaimahi and whānau work together to focus on the kaupapa, that is, a particular topic (area of potential change). This is similar to the whakatau stage of the pōwhiri potama model where the foundations to clarify the kaupapa, the history between us and what might get in the way are laid out so that a place of understanding about the kaupapa can be In MI this is not a one-off event – you may need to re-focus or negotiate a new focus if other seemingly important/relevant issues arise.

- Evoking (whakapuāwai) – the kaimahi works to bring forth the underlying motivations for the whānau wanting things to be different and their desire for

These motivations may emerge early in the session (for example, if the whānau has already given thought to the possibility of change) or may emerge as the session(s) progresses.

- Planning (whakamaheretia) – when the whānau is ready to change, the kaimahi and whānau work together to plan for how change might be brought about. Note this last process does not always occur in an MI session – you may not get to this point. Even if you do not get to planning, by engaging in the first three processes you are increasing the chances that the whānau may engage in behaviour change at some point.

Engaging, focusing and evoking are essential processes in MI. As long as the first three processes are present, along with the spirit of MI, then you are engaging in MI.

Ambivalence and Resistance

Ambivalence

Ambivalence essentially means ‘being in two minds’. Ambivalence is the normal reaction of any person who may be considering change. A person may on the one hand want to change (however, this is an unknown and invokes fear) and on the other hand may also want to remain the same (this may be making the person feel miserable but at least it is known and familiar). This is one reason why changing can seem so difficult. A person may want things to be different and at the same time find comfort in the familiar – difficult though it may be.

As mentioned, this should be anticipated by the kaimahi as a predictable internal state that the whānau may bring into the session. Within MI, ambivalence is not seen as a bad thing, but rather something that is normal and expected. The art is to turn this into a dance (move together gracefully) and not a wrestling match.

Resistance

E kore te tangata ngākau rua E u i ana hanga katoa

A person of two minds is unsettled.

Some older styles of working with people often involved putting the whānau in the ‘hot seat’ and using various methods to pressure or persuade the whānau into owning their problematic behaviour. The problem with this approach is that there is a natural human response – if a kaimahi adopts one position strongly the whānau will often take up the opposite position.

The difference with MI is that the whānau comes up with reasons for change and argues for them. Decision-making about any potential change is clearly focused on the whānau making the decision, not coercion or persuasion by the kaimahi. For this reason MI does not elicit resistance.

Resistance can present in a variety of forms – non-verbal, attitudinal and behavioural. The ability of the kaimahi to empathise with the whānau and appreciate how things are from their point of view is essential to minimise resistance. By accurately empathising with the whānau resistance is less likely to occur as there is nothing for the whānau to fight against.

An analogy which is sometimes used is the idea of dancing with a whānau as opposed to wrestling. If you notice you are getting stuck with a whānau (wrestling) it can be a reminder that you may be ‘getting ahead’ of the whānau – trying to solve the ‘problem’ before the whānau is ready for change or even sees that there is a problem.

What is the role of Kaimahi in Motivational Interviewing?

Hei whakatikatika i te huarahi

Guiding a process of transformation.

The role of the kaimahi is to create a therapeutic space where transformation or healing can occur. The kaimahi assists potential change by discerning tohu (signs) in the weather and conditions (so to speak), and guiding the waka (whānau) safely through the prevailing conditions to arrive at their destination.

He moana pukepuke e ekengia e te waka

A choppy sea can be navigated.

Change Talk

He kakāno koe i ruia mai i Rangiātea

You are a precious seed sewn from the highest heavens.

This whakatauakī describes our relationship to the creative source of all things. We are seeds sown in Rangiātea. As seeds we are full of potential, requiring the right conditions to flourish.

Any movement towards wellbeing is in and of itself a worthy goal to pursue. What this means in practical terms is that any movement a whānau makes towards oranga is a step of success.

Change Talk: Helping whānau move towards harmony

Change Talk is talk from the whānau about:

Preparing for change

Desire to change: “I want to control my drinking.”

Ability to change: “I know I can do it.”

Reasons for changing: “I want to be a role model for my children.”

Need to change: “I need to stop drinking – I just don’t want to live like this anymore.”

Implementing change

Commitment to change: “That’s it – I’m going to stop drinking now.”

Activation or preparing for change: “I’ve been thinking about what I can do instead of drinking.”

Taking steps: “I didn’t have a drink last night.”

A useful way to remember these signs of change is DARN CATs which uses the first letter of each of the types of change talk.

As you are learning to recognise when whānau are using change talk, remember that lack of sustain talk (talk about keeping things as they are) may not be the same as a commitment to change. For

some whānau it is rude to directly refuse a request. For these people, passively going along with the kaimahi may be misread as readiness to make changes.

MI can be really helpful because it helps kaimahi draw out motivations to change rather than trying to give whānau reasons to change. If you notice your whānau seems passive, you might need to back up and explore how the whānau is feeling about the possible change.

Change talk is important

- The more we hear ourselves say something, the more we believe it – the more a whānau uses change talk, the more they believe it.

- Research shows that when whānau use change talk, he or she is more likely to change their behaviour for the better.

- The more kaimahi can draw out change talk from whānau, and the stronger this change talk is, the more likely the whānau will make positive

- When your whānau are using change talk in sessions, you might think of them as moving toward

How can I encourage and strengthen change talk?

- Explore importance and confidence – see the Assessing Importance, Confidence and Readiness (page 23) for ways to explore how important it is for your whānau to make a change and how confident your whānau is that he or she can make that change.

- Explore how a whānau feels in (at least) two ways about their behaviour – see Exploring Values (page 27).

- Ask your whānau to imagine what might be the worst that could happen if they continue as they are (did not change their behaviour).

• Help your whānau imagine the future and remember the past.

“How might your life be different if you did change?” “What was life like before?”

• Explore goals and values and reinforce those which are inconsistent with their behaviour through your reflections

Reinforce change talk with reflections and summaries. Be careful not to get overly enthusiastic in case a whānau backs down and brings up reasons not to change.

Commitment language can vary in strength and determination. Whānau may be unsure of their commitment to make changes or may not be very determined to make changes. For example, if a whānau says, “I might stop drinking,” then the level of commitment is not very strong. This is important because when whānau are not very strong in their commitment to make a change, they are less likely to make successful and lasting changes. On the other hand, if a whānau says, “I am definitely through with drinking,” that is a stronger statement and the whānau is more likely to make positive changes.

- Ask a key question: “Where to from here?”

- Ask about the confidence of the whānau in the action plan.

- Work to improve the confidence of whānau in their ability to make a successful change.

- Work to draw out hope and

- Express your hope and optimism that your whānau will be able to make positive

- Remind them that you are available to help and can meet again for follow-up sessions.

Using Communication Skills to Facilitate Change

We all have many communication skills that have helped us work with whānau. The following focuses on skills to help create a healing environment for motivating positive change.

All of us have had an experience where what we said wasn’t what someone else heard – even though we thought we were being really clear.

Communication can go wrong because:

- the speaker does not say exactly what they mean

- the listener does not hear the words correctly

- the listener has a different understanding of the meaning of the

Reflective listening can help

Reflective listening helps to connect what the listener thinks the speaker means to say with what the speaker actually means to communicate. It is a way of expressing empathy. It conveys that you as kaimahi:

- accurately understand your whānau – being able to get a sense of what it would be like to walk in their shoes

- accept that feeling unsure about change is normal

- are accepting and non-judgemental of the whānau.

Reflecting what your whānau has said (verbally and nonverbally) is a necessary skill for using MI. When people feel understood, they are more likely to consider making changes.

Mā te hinengaro e kite, mā te whatumanawa e rangona

The mind is for seeing, the heart is for hearing.

Key Motivational Interviewing Skills: OARS

Ask open-ended questions

- Ask questions that cannot be answered with a “yes” or a “no”, and encourage whānau to say more than one or two word answers. Try to avoid closed-ended questions such as “Where did you grow up?” or “How much do you drink?” when you want to encourage storytelling.

- When asking an open-ended question, you do not know what the whānau answer will Using open-ended questions lets your whānau know that you want to hear their story. A few examples of open-ended questions are: “What has your drinking been like lately?”, “What have you liked about drinking?”

- Use open-ended questions to evoke change talk. For example ask evocative questions, such as “What concerns you about that?” Or ask for elaboration, such as “Why does that concern you?”

Affirm

- Affirm by saying something positive or

- Only offer support and praise or affirmation when it is sincerely

- You can affirm behaviours such as showing up for appointments or talking about difficult

- You can comment on the character of the whānau, such as being brave, being a role-model for future generations, or being honest.

Reflections

- Show the whānau you are hearing what they are

- Reflections are Make sure not to end reflections with a question mark, or inflect your voice upwards at the end.

- Start with “It’s…”, “It’s like…”, “You…”, “You feel…”, “And…”, “And you…”

- Try to capture the essence or meaning of what the whānau is

- Use reflection purposefully to evoke and strengthen change

- A good goal when you are first starting out is to try and reflect at least as much as you ask questions (that is, for every one question there is at least one reflection).

- Ideally your most common response to your whānau should be a For more information, see pages 15-16.

Summaries

- Summaries are like offering a bouquet or a koha. Reflect their kōrero by picking through all the things the whānau has said and only repeating back the In particular, include change talk, such as the client’s expression of reasons for change such as how drinking does not fit into their values or goals, etc.

- Summaries demonstrate to the whānau that you are

- Summaries are helpful when you want to transition to a new topic or introduce or change to a new strategy. For more information, see pages 16-17.

Providing information, advice or feedback

If you need to give your whānau information, advice or feedback, the PAPA formula is a great way to continue using MI and help your whānau hear and take in what you have to offer.

- Permission to discuss For example:

“Would you be interested in hearing about what high blood pressure means?”

“Would you be interested in hearing about what the recommended guidelines are for a healthy diet?”

“Would you be interested in knowing what your blood glucose level is and what that means?”

If yes, then continue to Step two: ask the whānau what they already know about the topic (see below). If no, respect the wishes or your whānau and refrain from giving the information, advice or feedback. There is no point in doing this if they are not ready or able to hear. - Ask the whānau what they know about the topic For example:

“Tell me what you already know about safe drinking levels while driving.” “What have you been told already about drinking and pregnancy?” “What do you already know about how your accident happened?” - Provide information, advice or feedback in a neutral way and non-judgemental manner

For example:

“It has not been proven that there is any safe level of drinking during pregnancy. So, the safest bet is not to drink at all to have the healthiest baby possible.”

It can be useful to begin by acknowledging that what you are about to say may or may not fit with your whānau.

For example:

“I don’t know whether this will make sense to you or not, but these are some things that other people have found helpful to reduce their drinking.” - Ask the whānau what they think about what you have just said For example:

“How how does that fit with how you see things?” “What do you make of that?”

“Where does that leave you now?” - Ethical issues: If you feel you need to tell the whānau information for ethical reasons (e.g., if suicide or homicide is imminent, or child or Kaumātua abuse are brought up), do not ask their permission at the beginning. Instead, begin with a statement of concern.

For example:

“I am very concerned about you and feel the need to share my concerns with you.”

Reflective Listening: A key Motivational Interviewing skill

Māori have a strong oral tradition. Using MI, you can encourage your whānau to tell their own story, to learn more about their life journey and how their behaviour can get in the way of having the life they desire. As a kaimahi, you can use your skills of listening to whānau. Being a good listener helps you let whānau know you have heard and understood them.

In MI the ability to use reflective listening (puna ora) starts with being a good listener and a good communicator.

Here are some suggestions to help you with reflective listening.

- Hear what the whānau is saying

- Make a guess at the underlying meaning, energy, and emotion whānau are trying to convey

- Choose your direction – guide the whānau. What are you going to respond to and what are you going to let go by? Remember, we want to encourage change talk and to decrease sustain talk.

- Make your reflection a statement instead of a question (don’t inflect at the end).

Types of reflective listening

Simple reflections: stay close to the kōrero of the whānau; they may be most helpful at the beginning of sessions, when a whānau is angry, or to encourage the whānau to clarify a word or feeling.

Repeat: Saying exactly what the whānau said using the same words.

Whānau: “It almost feels like my husband is judging me.”

Kaimahi: “Your husband is judging you.”

Rephrase: Staying close to what the whānau said, but in different words. A rephrase is like a synonym.

Whānau: “It almost feels like my husband is judging me.”

Kaimahi: “Your husband is critical of you.”

Use simple reflections as one of a range of listening skills.

Complex reflections: can help increase the pace and give direction to the session by helping whānau get to the heart of the matter. A good goal is to use more complex rather than simple reflections.

Add information to what the whānau said, such as underlying emotions or feelings, in order to get a better understanding of their meaning. The kaimahi infers the meaning the whānau is expressing.

Whānau: “It almost feels like my husband is judging me.”

Kaimahi: “You’re afraid he doesn’t like what he’s seeing in you.”

Double-sided reflection: is where you reflect back both sides of the ambivalence the whānau is expressing. It can be a particularly useful complex reflection. It is a good idea when using a double- sided reflection to present the sustain talk first and then the change talk, and to combine these with “and” or “and on the other hand” (rather than “but”).

Whānau: “I want to give-up for my tamariki but I just don’t know that I can do it.”

Kaimahi: “Part of you is not sure you can make this change and another part of you sees this as important to do for your tamariki.”

Overshooting and undershooting for direction: reflecting the extreme is a strategic way to get the whānau to say more or less about something.

- Overshoot – you want the whānau to ease up in their intensity. This is useful when a whānau is speaking sustain talk and you want to decrease

- Undershoot – you want to draw out more intensity from the whānau. This is useful when you want more change talk.

Whānau: “It almost feels like my husband is judging me.”

Kaimahi: “You’re worried he thinks you are no good at all.”

(Overshoot: whānau might agree and burst into tears. Or may decrease intensity by disagreeing with such an extreme statement and go on to explain how her husband is upset about her drinking.)

Kaimahi: “He’s been a little critical of you.”

(Undershoot: likely that whānau will disagree and explain in detail and more intensity the concerns her husband has about her drinking, and how he is being critical.)

Using metaphor: can be a good way to show you understand what the whānau is saying.

Whānau: “It almost feels like my husband is judging me.”

Kaimahi: “He’s the judge and you’re on trial.”

Summaries: are a type of reflection that involve pulling together what you have heard from the whānau from different parts of your conversation with them, especially change talk. A summary can be thought of as a bouquet of flowers, with the flowers being their change talk which you gather together into the summary (bouquet) and you hand back to the whānau.

Interim (or mini) summaries are pulling together statements your whānau has shared and presenting them back to them, before you continue on.

Kaimahi: “You’ve said that your husband criticises you in front of others, compares you to skid-row alcoholics, and tells you you’ll never amount to anything. What else have you noticed?”

Transitional summaries are pulling together statements so you can change course or shift focus (guiding). For example, you might want to guide the whānau from talking about the positives of drinking to the negatives of drinking. Another change might be from building motivation to change to increasing commitment to change.

Kaimahi: “Okay. So let me see if I’ve got this straight. Your husband’s criticism has become too much, it’s affecting your self-esteem, and you’re worried that your daughter is learning that it is okay to mistreat women.”

Concluding summaries are pulling together what the whānau has said during your conversation. It is definitely good to include the change talk you have heard. Whether or not you include sustain talk is up to your judgement. It may depend on how strong

it is and whether your whānau is still feeling ambivalent about change. If you decide you do need to include sustain talk, it is a good idea to present this first in your summary and then give the change talk.

Kaimahi: “Okay, so from what you have said today, your husband’s criticism has become too much, it’s affecting your self-esteem, and you’re worried your daughter is learning that it is okay to mistreat women. Some of your husband’s criticism about you stems from his concern about your drinking. And you have started thinking that maybe it would be a good idea to make changes to your drinking as you are concerned about what it might be doing to your tamaraki.”

It can be useful to finish transitional and concluding summaries with a question, checking out where the whānau is at, as part of handing the bouquet (summary) back to them.

For example “Where does that leave you now?”

Judging the quality of reflection: instant feedback from whānau

- If your whānau keeps talking and gives you more information, that is a good sign for the quality of your reflections.

- If your whānau talks less in a way that seems to be closing down, then that is not a good sign. (See “Are your MI skills improving?” pages 38- 39).

When Whānau Put the Brakes On

It is normal for whānau to show signs of ambivalence early in their contact and even as sessions progress. Ambivalence can occur when the whānau is unsure whether he or she has a problem, or is uncertain that he or she wants to do anything about it. Your whānau may not be sure whether you can help them. Your whānau may

be worried they won’t be able to make positive changes and will ‘fail’. Or your whānau may have some concerns about what change will mean for them.

Discord is a signal to you that you are not working well together. The following are signs of discord:

Challenging

Whānau: “Do you even speak Te Reo?”

Whānau: “You have no idea what it’s like – have you ever have a drinking problem?”

Interrupting

Whānau doesn’t let the kaimahi finish talking.

Disagreeing

Whānau: “You don’t know what you are talking about.”

Whānau: “That just wouldn’t work for me.”

Changing the subject away from the discussion of change

Whānau: “What do you think about those health care budget cuts?”

Ignoring or not following

Whānau seems to be daydreaming or bored.

Sustain talk

Sustain talk describes when whānau are treading water rather than moving toward positive change. Sustain talk makes it less likely that whānau will make positive changes. The whānau may use sustain talk to indicate: their desire to stay as they are; their worries they will not be able to change; reasons to not change; the need to stay as they are; or a commitment to continue to stay as they are. For example:

Desire to maintain alcohol and other drug use as it is without making changes

Whānau: “I want to keep drinking like I am.”

Inability to change: lack of confidence in ability to make a successful change

Whānau: “I’ve tried before; I just can’t stop.”

Reasons for not changing:

Whānau: “I don’t need to change; my drug use isn’t that bad.”

Whānau: “My health is still good, so I’d rather keep drinking.”

Need to remain the same:

Whānau: “I’ve got to keep ”

Whānau: “I need alcohol.”

Commitment to remain the same:

Whānau: “I am going to keep drinking, and no one can stop me.”

Activation towards remaining the same:

Whānau: “I saved up my money so I could afford to buy alcohol this week.”

Taking steps towards staying the same:

Whānau: “I went on a drinking binge last weekend.”

As kaimahi, our goal is not to draw out sustain talk but to draw out motivations for change (change talk). If we are only drawing out sustain talk from whānau, they are more likely to stay the same.

Responding to sustain talk

Reflective responses

Use these to techniques to “roll” (acknowledge and accept) with the sustain talk, rather than trying to fight against it. Try not to give whānau any material to argue against – even if they seem like they are trying to pick a fight. Avoid getting into a wrestling match with whānau, with each of you trying to overpower the other. Try to use the energy from the whānau to figure out what they are trying to tell you. For example, whānau are often worried that you will judge them or that you won’t be able to help them and they won’t be able to succeed in making changes.

The following are some useful responses:

Simple reflection

Repeating or rephrasing what the whānau has said. Repeating can help when you want more information (for the whānau to clarify what they have said) or when you want to be sure you heard them or show them that you have understood what they are saying.

Whānau: “This whole thing has been so confusing.”

Kaimahi repeats:

“Confusing” (to invite the whānau to tell you more about how it is confusing)

Kaimahi rephrase:

“It’s been hard to make sense of your situation.”

Complex reflection

Trying to get at the underlying meaning of the words the whānau is saying, which often includes a guess at what your whānau might be feeling.

Whānau: “You’re not from around here. What do you know?”

Kaimahi: “You’re worried that I might not understand you.”

Double-sided reflection

Especially useful when whānau feels mixed about making changes, for example, the whānau both likes some things about drinking and also dislikes some things about drinking. Remember to use “and” as you reflect both sides (for example, likes and dislikes or pros and cons).

Whānau: “I am tired of dealing with the courts but I really enjoy drinking with my friends.”

Kaimahi: “Both things are true – you like drinking with your friends and you’d rather not have to go to court anymore.”

Reframe

When you would like to invite the whānau to think about a different interpretation or take a different perspective.

Whānau: “My wife is always nagging me about my drinking.”

Kaimahi: “Your wife is concerned about you.”

Agreement with a twist

You agree with the whānau to a degree and add new information that invites a new perspective. You can think of it as a reflection followed by a reframe.

Whānau: “You probably think you know it all and I’m just another addict to you.”

Kaimahi: “You’re right that one-treatment- fits-all probably won’t work; we need to work together to personalise it to you.”

Emphasise personal choice and control

When you and your whānau get into a power struggle or the whānau feels like you are going to make them do something they may not want to do (change their behaviour, seek treatment, a homework assignment), it is helpful to remind

the whānau that they are in control and it is up to them to make the decisions. Even if we wanted to force people to change, we probably wouldn’t be successful – especially in the long run. Change has to come from within.

Whānau: “You’re the boss – just tell me what I have to do and I’ll do it.”

Kaimahi: “Well, it’s really up to you and what you think will work best for you. I will do my best to work with you to help you make a decision that is right for you.”

Whānau: “Do I have to get drug tested?”

Kaimahi: “That is a requirement to be in our treatment programme but it is still your choice. If you like, we can explore the pros and cons of your options.”

Traps to Avoid – Ngā Hīnaki

Here are some things that don’t fit well with using MI. These are “traps” because they can keep both the kaimahi and, more importantly, the whānau stuck rather than moving toward change. The following traps interfere with our ability to use MI:

Question-answer trap

The kaimahi gets trapped asking question after question to try to get information and the whānau gets trapped in passively giving short answers. The problem with this trap is that whānau get used to providing short answers and being passive. Then it can be hard to help them open up.

If you have a lot of questions or forms to complete, it can be helpful to begin with a time of exploring using MI before filling out the forms.

This trap sometimes happens when the kaimahi asks a series of closed ended questions.

For example:

“How many times did you drink last week?”

“How many drinks do you have each time?”

“What kinds of drinks do you have?”

Confrontation-denial trap

The kaimahi gets trapped into confronting whānau with their problems and whānau get trapped into denying they have a problem or asserting it’s not really that bad. Denying is sustain talk and decreases the chances the whānau will change.

This sometimes happens when kaimahi feel it is really important for a whānau to admit to having a problem.

For example:

“Can’t you see how your drinking has hurt different parts of your life?”

“You need to stop denying that you have a drinking problem!”

Expert trap

The kaimahi gets trapped trying to prove their knowledge or expertise, or show that they are in charge and have the answers. The whānau gets trapped in a passive role or becomes angry that the kaimahi does not respect his or her strengths and knowledge.

For example:

“You don’t realise how bad your life is going to look in a few years if you keep up this drinking.”

“I know what you need to do to get better.”

Labelling trap

The kaimahi gets trapped delivering bad news and waiting for the whānau to accept the label, rather than meeting them at level of readiness (see page 24 for how to assess this). The whānau either passively accepts the label or gets defensive and angry, which is associated with not changing behaviour. This sometimes happens when kaimahi feel like they have to put a label on behaviour they are seeing.

For example:

“The way you are drinking makes you an alcoholic.”

“You have alcohol dependence.”

Righting reflex

As helping practitioners and kaimahi we may have a strong desire to help other people. This desire can lead to a tendency to want to put things right, fix things, or make people better. This runs the risk of the kaimahi focusing on solutions before the whānau is ready. In MI the kaimahi tries to Resist the righting reflex by trying to Understand the motivations of the whānau, Listening and Empowering them. A useful way of remembering this is RULE which uses the first letter of each of the key words.

Motivational Interviewing Strategies

This section is divided into two phases with the first being strategies to build motivation for change, and the second being how to strengthen whānau commitment to change.

If your whānau does not seem ready to change, it may be helpful to use strategies from Phase 1. However, if your whānau seems ready to make changes, then start with Phase 2 strategies. If you are using Phase 2 strategies and your whānau is not following through with the change plan, or is voicing concerns about changing or reasons to stay as they are, it may be helpful to go back to some Phase 1 strategies.

Remember, these strategies are only guidelines and do not have to be followed exactly. Again, your whānau will be your best guide. These strategies are designed to help whānau talk about what is happening for them, and to evoke and strengthen change talk, while at the same time keeping sustain talk to a minimum, and not eliciting resistance.

Remember the spirit of MI needs to be present when using these strategies – if used in isolation, without the spirit, then it is not MI, and is not likely to be as effective.

The relationship between kaimahi and whānau is found to be very important in helping whānau achieve positive outcomes. The following are key aspects to developing a positive relationship.

Be present: let whānau know you care about them

Listen intently to your whānau; try to make them feel as if they are the most important person in the world during your time together. Try to demonstrate your willingness to be there with your whānau. Try to let yourself be used as an instrument of healing in service to them. Create a healing space – ‘kai, wai and karakia’. Examples of manaaki and aroha can be simple, truthful statements of your concern about the effects of substance use; your wish for their best well-being; and other statements that notice the personal and communal strengths of your whānau.

Let whānau know that you are on their side and want what’s best for them.

Using the MI approach, it is important to let the whānau know that you are on his or her side. How do you do that? What about those whānau who are clear that they do not want to be in therapy (forced into treatment by court or loved ones) or for those who are really nervous or unsure about whether they have a problem or what they might have to do in counselling? Especially in early sessions, it is important to use reflections when whānau are angry or resistant. Usually when a whānau hears that you have understood what they are communicating, they feel freer to move on to another topic.

For example:

Whānau: “I don’t need to be here and you probably can’t help me.”

Kaimahi: “You’re not sure you have a problem and you are worried that I couldn’t help you even if you did.”

These kinds of kaimahi responses can help whānau move on to another topic rather than arguing with you about whether they have a problem or whether you can help them or not. These kinds of kaimahi responses can help whānau feel safe.

Ngākau māhaki: be accepting and non-judgmental

Remember to acknowledge your whānau as people rather than a problem. For many Māori, this includes acknowledging them holistically to include their hinengaro (mind), tinana (body), whānau (family) and wairua (spirituality). Accepting your whānau does not mean you have to accept any behaviour that is unacceptable. When whānau share

difficult experiences, especially if they feel whakamā or afraid of negative judgment, it is important to be supportive of them.

Involve the whānau in setting goals

You want to be working together with your whānau toward the same goals without imposing your own goals on them. As you work with your whānau he, she or they may develop new goals as you work together to increase motivation to change. In MI, part of being directive is helping move whānau along towards positive change. Of course, we respect whānau choices so it is good to remind them (and ourselves) that whatever they choose to do is up to them.

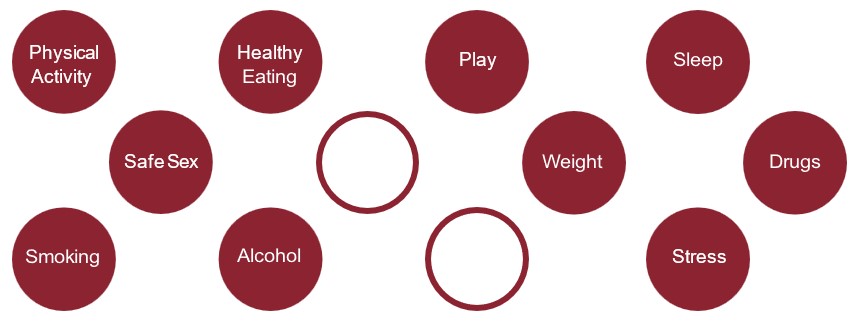

Deciding on a topic or target behaviour

When beginning with a whānau, it can be helpful to involve them in setting an agenda. If you have the flexibility to discuss a variety of topics, you might use a form like the one below or just use the statements below as you talk with your whānau. This form was developed for doctors and other medical professionals who do not have much time with whānau. This form is just to give you an idea of how to work in partnership with your whānau when deciding what to talk about first, and can be changed to fit in with topics you usually discuss with your whānau.

- Ask permission

“Would it be alright if we spent the next 5-10 minutes talking about your health in general, the things you do to maintain it, and what, if anything, you might like to change?” - Explore current strengths

“Tell me about the things you currently do to keep yourself healthy.” Add new behaviours to the blank circles below. Cross out irrelevant items if mentioned. - Agenda matching

“These are the things you mentioned as well as other common things others mention. I’m wondering if you would be interested in exploring one of these areas. Or perhaps there is something else that hasn’t been mentioned that you consider more important to your health right now?” - Explore reasons

“Tell me about that. What made you select that behaviour? What are your thoughts about it?”

Assessing importance, confidence and readiness

Goals:

- To provide an opportunity for whānau to explore and realise their own motivations to change a specific behaviour.

- To provide the kaimahi with an opportunity to draw-out and reinforce change

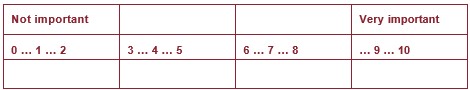

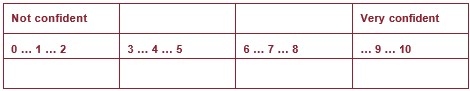

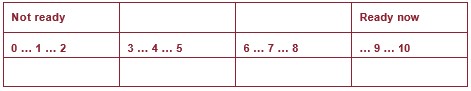

Depending on your whānau, you may use only one of these rulers, all three or any combination. We encourage you to pay close attention to the wording of the questions provided below because it can help you draw out change talk rather than sustain talk from your whānau.

Measuring the importance of change

- “On a scale of 0 – 10, where 0 is not at all important and 10 is extremely important, how important is it for you to change (specific behaviour) now?”

- “What makes you choose (number whānau chose) rather than a 0?” (Note: this draws out the change talk)

(Be very careful NOT to ask, “What makes you choose a (number chosen) rather than a higher number?” This question will encourage the whānau to give you reasons it is not more important to change. It is not a good idea to encourage whānau to tell us why it isn’t important to change because then they are less likely to make positive changes.) - “What would it take to bump you up a few notches to a (choose a number two or three higher than originally given)?” For example, “What would it take to bump you up a little from a 3 to a 5?” This kind of question draws out more change talk, and helps the whānau imagine the change becoming more important. (Take care NOT to make this number a lot higher than the one the whānau gave you, as this may lead them to feeling pushed by you (that you expect them to consider it important).

Listen carefully through this process, use reflection and small summaries.

Measuring confidence to make a change

- “On a scale of 0 – 10, where 0 is not at all confident and 10 is extremely confident, how confident are you that you could make a change in (specific behaviour) now?”

- “What makes you choose (number whānau chose) rather than a 0?”

- “What would it take to bump you up a few notches to a (choose a number two or three higher than originally given)?”

Measuring readiness to change

If it seems helpful with your whānau, and the importance and confidence for change is reasonably high (7 or higher on both scales) you may use the same questions for readiness to make a change now.

Summarise (highlight reasons it is important to change, what makes them confident they can make changes and what makes them ready to make those changes now, being careful not to make them seem more ready than they are).

Express confidence in them and appreciation.

The following is an adapted version of the rulers that does not include numbers and only uses descriptions, which might suit some whānau. For each ruler, just change the wording to match what you are asking about: importance of making a change, confidence to make a change, and readiness to make a change.

Exploring good things and less good things or pros and cons to evoke change talk

Goals:

- To provide an opportunity for your whānau to actively discuss how they feel about a specific behaviour (for example, smoking).

- To provide the kaimahi and the whānau with an opportunity to: understand the point of view of the whānau about the pros and cons of their behaviour, to reinforce change talk, and to support the whānau.

- Ask the whānau what they like about their behaviour (not changing).

“What are the good things about smoking?”

“What do you like about smoking?” - Listen, reflect, and ask them to tell you more.

- Ask what they don’t like about their behaviour (asking for change talk).

“What are the less good things about your smoking?”

“What do you dislike about you smoking?” - Listen, reflect, elaborate, and get the full picture.

- Summarise both sides, with the reasons to continue as they are (sustain talk) and finishing with the reasons to change (change talk).

- Ask the whānau some version of “Where does that leave you now?”

- You may also wish to affirm the whānau for having the discussion, express appreciation, confidence, and support.

Asking whānau what they like about their behaviour helps build rapport and gives you information about reasons for the behaviour that may be helpful in treatment planning. For example, if they smoke to relax, they might be interested in learning other ways to relax besides smoking. Again, your whānau are your best guide.

Asking about the good things and less good things about the behaviour (rather than the pros and cons) may be useful if your whānau does not seem to be seeing their behaviour as a problem.

Exploring values

One of the principles of MI is to help whānau discover, explore, or share the conflicts between their lives with their current behaviour and what they would like their lives to be like. Exploring the values of your whānau can help them see ways their behaviour is getting in the way of them living the life they would like to have. An example of drinking causing a conflict with important values occurs when being a good parent is one of their top values, but they have lost custody of their children due to drinking. When your whānau brings up such a conflict, remember to be warm and caring and to allow the whānau to think about what it means to them to have this conflict. Finally ask your whānau what they would like to do about the conflict, if anything.

Goals:

- To help your whānau think about their core values and help you understand these values.

- To provide an opportunity for your whānau to think about how their behaviour fits with or interferes with their core values and what is important to them.

If you would like to use a set of values on cards to help whānau think about their top values, here’s a brief description.

There are a set of cards listing values such as ‘acceptance’, ‘beauty’, ‘family’, and ‘spirituality’. Whānau sort the cards into different piles based on how important they are to them. The goal is to rank the top ten most important values for further discussion. A number of practitioners have been developing value cards based on Māori concepts and beliefs.

You can find a set of values on cards at the website: www.motivationalinterviewing.org. Note there are two different sets of values cards available – select the one you think will fit your whānau best. There are also some blank cards so whānau can write their own values if these are not captured on any of the cards supplied.

You can also access the Kōrero mai Talking Therapies Resource produced by Te Puna Hauora ki Uta ki Tai. These cards cover a wide range of emotions, feelings and states of being.

Key elements

- Ask your whānau to select or talk about values that are most important to him or her at this

- Ask your whānau to tell you what the values mean to them and why they are important.

- Try reflections to gain a deeper understanding from the perspective of your whānau.

- Listen and reflect

- Ask a neutral question about how their behaviour fits into the life and values of the whānau.

- Use reflections and then summarise when you think the whānau has explored this thoroughly or is ready to move to another topic.

Avoid:

- judging

- arguing

- pointing out conflicts between their behaviour and values

- making assumptions about the values of the whānau

- telling the whānau your values about the

Some helpful questions:

- “Tell me a little about each one of these values. What does it mean to you? What makes it important to you?”

- “I’m wondering how your alcohol use fits with this picture?”

- “You’ve said that is important to you. How, if at all, does using drugs fit into that?”

Affirming whānau – whakamana

Goal: To communicate that the strengths and efforts of whānau are noticed and appreciated. Keep in mind that being honest and sincere will make your affirmations powerful.

Lightweight – affirmations of support and appreciation

“I know it can be difficult for you to get here, thanks for coming on time.”

“I must say, if I were in your position, I might have a hard time dealing with that amount of stress.”

“I can see how that would concern you.”

“You’re working hard to restore harmony in your family and community.”

“That sounds like a good idea.” “I think you’re right about that.” “I think that could work.”

Heavyweight – affirmations of whānau strengths or character

“You are the kind of person who cares a lot for other people.”

“You are very creative. It shows a lot about what kind of person you are.”

“You have what it takes to be a leader. Other people listen to you.”

“You are the kind of person who does not like to talk about other people when their backs are turned. You have a lot of integrity.”

“You like a challenge. You have what it takes to overcome difficulties.”

“You’re a deeply spiritual person in all aspects of your life.”

“You care about your family and your community. Your role is important to you.”

Timing: recognising signs that the whānau is ready for change

If you see these signs in your whānau, try using the following strategies to strengthen commitment to change. If you do not see these signs or can tell that the whānau is still not ready to make changes, then continue to build motivation to change.

- Good engagement and

- Decreased sustain

- Decreased discussion/questions about the

- Resolve – whānau does not seem conflicted but seems to have decided to change.

- Increased change

- Questions about

- Envisioning: thinking about how the change might happen or what life might be like after

- Experimenting: whānau begins trying to take steps or is taking steps to change.

Moving to talk about how change might occur

- Summarise reasons the whānau has shared for not changing and end with reasons to change.

- Ask key questions such as “What’s next?” and “Where do we go from here?”

- Pay attention to commitment language (examples include “I might stop drinking”, “I’m never going to drink again”) and positively reinforce (for example, “That sounds great given your thoughts about how drinking has gotten in the way of your family life”).

Creating an action plan

Negotiating a change plan (only if they are ready, otherwise whānau will likely have a set back in their motivation to change)

- Setting short-term and long-term goals together (make sure they are the goals of the whānau and that each goal is measurable and specific; no alcohol for one month; go to 90 meetings in 90 days, etc).

- Considering change such as abstinence versus reducing drinking and western in-patient treatment versus traditional healing and out- patient treatment (can brainstorm; list pros and cons).

- Arriving at a plan: evaluating how various plans may turn out – what might help the plan be successful and what might get in the way of

- Drawing out commitment and confidence

- Expressing confidence and

- Affirming the strengths of whānau and steps taken toward change.

Remember it is best to work on an action plan once you feel your whānau has expressed a commitment to make a change. When we get ahead of our whānau and try to make an action plan for change before they are ready, they tend to have more difficulty making those changes. Once your whānau is ready to make a change, here is one way to think about helping them plan for that change.

Draw the goal from the whānau

- “What do you think you will do now?”

- “What is the change that you would like to make?”

- “Where would you like to go from here?”

Explore options

- “What ideas do you have about how to reach that goal?” (short-term and long- term)

- “What kind of lifestyle changes have you been successful with in the past?

- “What helped you successfully make that change? How do you think you might be able to apply those skills to this situation?” (This helps to build confidence in a whānau making a new change.)

- “Would you be interested in hearing about things that have worked for other people?”

- “What do you think about those? What fits for you?”

- “How will you know if the plan is or is not working? What will you do?”

If you want a worksheet, then you might decide to help the whānau complete the change plan worksheet below.

NB: If you used the confidence rulers (page 23) and found your whānau reported a confidence level below 8, encourage a change in the plan to ensure increased confidence. A few ideas for your consideration are:

- helping build confidence by asking the whānau about previous successful changes

- discussing adding more support from family and friends

- exploring thoughts about avoiding ‘risky’ situations where engaging in the problem behaviour will be more tempting

- Perhaps adding a time limit to the goal at which you can check in with each other and renegotiate (for ‘no alcohol for 90 days’ may not seem as overwhelming as ‘a lifetime of no alcohol’ and may help your whānau start on a path of sobriety).

Summarise the plan. Include the main reasons for the change and the details of the plan.

- Ask about commitment – “Is this what you are going to do?”

- Remember that some people are more likely to agree with you as their kaimahi only because they do not want to disagree with you or disappoint While it is very important to trust what your whānau says, it may be important to pay attention to your own feelings that your whānau may be trying to please you more than express what is true for them.

- You may want to share your feelings with your whānau in a supportive and gentle way. For example:

“I hear what you are saying and I would like to share a concern with you. Sometimes people agree with their kaimahi to be polite or because they like them and that’s nice but might not be the best way for a whānau to reach their goals. If you aren’t sure about something I say or suggest, I hope you would feel comfortable telling me. I really want what’s best for you.”

If you hear commitment, reinforce If you do not hear commitment, you might ask your whānau whether the plan needs any changes or ask what would help them feel more committed to change.

Change plan worksheet

The following are some examples of how to fill in this type of change plan worksheet. On the

next page there is a blank form in case you would like to use it with your whānau. As you fill out the plan, whānau may get nervous and express mixed feelings about making the changes or whether they can be successful. This is normal and you might share this with your whānau. As you hear mixed feelings, it can be important to be flexible and move back to reflecting mixed feelings or working on increasing confidence to make changes. It might be helpful to remind whānau that you both can continue talking about the action plan and make changes as needed in future sessions together.

- The changes I want to make (or maintain) are:

- no drinking alcohol for 90 days: (until 31/3)

- increase physical activity such as walking

- help my mum cook meals at hui (until 31/3).

2. The reasons I want to make (or maintain) these changes are:

- I lost my job because of showing up too hungover and missing too much work

- I want to become fitter so I am a good role model for my children and moko

3. The steps I plan to take in changing are:

- attend counselling sessions once a week for the next 90 days (until 31/3)

- walk with my friend three times a week for 30 minutes (until 31/3)

- let mum know I would like to help whenever we have whānau or hapū hui (until 31/3).

- The other ways people can help me are:

4. The other ways people can help me are:

eg. Mum can teach me to cook; listen when I’m having a hard time

5. Some of the things that could interfere with my plan are:

- if I can’t hang out with my drinking buddies at night

- if my friend doesn’t want to

6. My backup plan is working if:

- my friends ask me to go out drinking and I will tell them I am not drinking but would like to do something else for fun.

7. I will know if my plan is working if:

- I am not drinking alcohol

- I am creating a new life for myself and my

Finish by ask how confident your whānau is that he or she can reach these goals. You can use the confidence ruler (page 23) if you like.

Change plan worksheet

- The changes I want to make are:

- The reasons I want to make these changes are:

- The steps I plan to take in changing are:

- The ways other people can help me are:

- Some things that could interfere with my plan are:

My back up plan is:

I will know that my plan is working if:

Closing the conversation

• Express your confidence

“Wow, we’ve accomplished a lot today. You have developed a good plan with a backup if it doesn’t work. You have had successes in the past and have a lot of strengths and skills you can use to achieve your goals. My experience with whānau similar to you is that once the decision has been made, they have found a way that works for them. I’m here to help in any way I can.”

• Show appreciation

“Thank you for all your hard work today. I look forward to seeing you next time.”

Hazards to avoid

These things are likely to set whānau back rather than help them move toward making positive changes.

- Underestimating mixed feelings about change: trying to move forward when your whānau still feels unsure about changing. This can lead to the whānau resisting change. When a kaimahi pushes the whānau to make a change plan before they are ready, the whānau has greater difficulty making and maintaining changes.

- Over-prescription: telling the whānau what to do rather than helping the whānau make a plan.

- Not providing enough direction for your whānau; not offering guidance when needed; simply reflecting anything the whānau says rather than carefully selecting important information related to their behaviour and changing it.

MI strategies overview

Below is a guide that combines many of the previous strategies listed to give an idea of a sample session. This guide has more details about what to do depending on how important it is for your whānau to change and how confident they are they can make a successful change.

- Negotiate the agenda

- Ask permission to discuss a particular

- Ensure you share the same agenda (matching) as your whānau.

- Use an agenda matching chart (page 22) to help agree on an agenda if appropriate.

2. Assess importance and confidence

“To help me understand more about how you feel about your drinking, I would like to ask you some questions. On a scale of 0-10, with 0 being not at all important and 10 being very important, how important is it to you to ?” (make changes in your drinking; reduce your risk of alcohol-related injuries, etc).

“What made you choose a (number chosen) and not a 0?”

“What would it take for you to move from a (number chosen) to a (slightly higher [two points] number)?”